This page was conceived after the final-year students of 2004/2005 invited me to speak to them about how to become a surgeon in Nigeria. What are the academic and other requirements for a medical graduate to become a surgeon in Nigeria?

The practice of medicine in Nigeria and other developing countries may be more difficult than in the West for a number of reasons that are unique to these nations.

The various reasons include:

- Poverty: The most important reason. Poverty makes it tough for governments to provide decent healthcare facilities and for people to pay for the available treatment

- Inadequate medical facilities that commonly result in unsatisfactory outcomes and unhappy patients.

- A cultural attitude that glorifies traditional healing despite the fact that many of the practitioners’ claims are unsubstantiated.

- Religion: Like most nations in Africa, people living in Nigeria have a strong tendency to look for religious or quasi-religious cures for their illnesses. Of course, poverty and lack of education play a role in this.

- Poorly regulated medical environment where unorthodox practitioners are free to advertise their practice while orthodox medical practitioners are prohibited from doing so.

If you’re interested in becoming a surgeon and believe surgery is a good fit for you, you should ask yourself a very essential question: “Is surgery a good fit for me?”

My Story

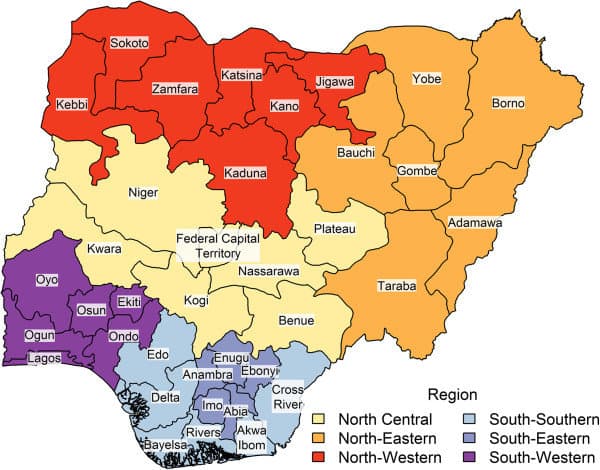

Growing up, I wanted to become an engineer. As a child growing up in Sokoto Village near Owena in the state of Osun, NI made my own toys. As a result, I would make a toy truck with a body comprised of flattened Peak milk tins and wheels made of discarded rubber sanders. We made our own kites, roll-along wheels, and Christmas crackers, which we proudly referred to as rackets! Consequently, I grew up learning to make things by hand. The most fascinating item to me at the time were the wooden-bodied passenger trucks that visited the village every day. My ultimate ambition was to make one of them. When I learned that engineers were responsible for their construction, my ambition was solidified!

Then, fate intervened. After sustaining an injury in the village, I was admitted to the Wesley Guild Hospital in Ilesa. I required surgery, and the surgeon who performed it left such a profound impression on me that I’ve decided to become a surgeon when I grow up.

As the saying goes, the rest is history.

Is Surgery a Good Fit for You?

Four years after registering for a particular specialty, there is a high rate of abandonment, according to studies conducted in the United Kingdom. Surgery was rated among the specialties with the highest rate of drop out. Low job satisfaction in a given specialty is attributable to an inadequate understanding of what the specialty entails. Consequently, your motivation and expectations will significantly impact your future job satisfaction as a surgeon.

Surgeons keep long hours. Surgeons perform surgeries and will see blood in the course of their work. Some surgeons like plastic surgeons and trauma surgeons routinely come across truly gruesome injuries. Others must work with pus and other contaminated and smelly body fluids. So, if you’re squeamish, surgery may not be for you.

Therefore, think carefully and consult your teachers to determine if surgery is right for you.

Who then is a (Good) Surgeon?

I am not going to talk about the definition of who a surgeon is. If you’re reading this article, you have a rough idea of who a surgeon is. What I am going to talk about here is what makes a great surgeon. According to the American College of Surgeon, a good surgeon must have the following attributes: Intelligence, professionalism, conscientiousness, creativity, courage, and perseverance on behalf of their patients.

Therefore, a good surgeon must have the following attributes:

- A surgeon must care for others, including both patients and coworkers.

- He must be able to communicate with patients, their families, and team members.

- He must be willing to both learn and teach.

- When learning or instructing others, he must be both patient with himself and those he is instructing.

- The surgeon must be inquisitive and understand ongoing surgical research and development procedures.

- He should have the stamina required for lengthy operations and challenging obstacles.

Surgery is the red flower that blooms among the leaves and thorns that are the rest of medicine.

Tradeu

The Joy of Being a Surgeon

I’ve been a surgeon for over twenty years. Wonderful, difficult, fascinating, exhausting, overloaded, and time-consuming. Surgery is not merely a profession; it is a calling. If I had to choose again, I would select surgery, not because it pays well, but because of what it means to me, my patients, and my students. Surgery is one of the few professions in which one can simultaneously serve as a healer, educator, scientist, and mentor. As a surgeon, you are also a detective, attempting to unravel the puzzle is the patient’s condition. Surgery is the joy you see on your patient’s face when you inform him that he is cured. That is priceless!

However, surgery has a dark side as well. To become a surgeon is a difficult endeavor. After your training, you must remain current on new developments. You simply must keep reading! You are on call when others are home. You miss significant dates, such as your daughter’s birthday, your son’s graduation, and your wedding anniversary. All of them are sacrificed on the altar of duty and obligations. And one of the most difficult things anyone can be called to do is to inform a wife that her husband has died, a father that his son has passed away, or a cancer patient that he has a limited amount of time to live.

However, such is life. So, surgery is like life itself. There are both good and bad times. In my opinion, the good times outweigh the bad ones. I absolutely love my job as a surgeon.

You know, maybe I shouldn’t say everything. How about we hear from some of the world’s most esteemed surgeons on the joy of being a surgeon?

“I have never regretted going into medicine. I’d do it again tomorrow, and I tell that to any youngster who is considering it. Medicine is a calling. It is more than a business. One can make money doing other things. But I chose medicine–surgery–because it combined a quest for knowledge with a way to serve, to save lives, and to alleviate suffering.”

–C. Everett Koop, MD, FACS, Pediatric Surgeon and former U.S. Surgeon General

“When a patient gets well his doctor ‘feels’ good–a personal warm glow that tells him once again what being a doctor is. This pleasure never dulls with age or time, but remains vital and strong after decades of practice. ‘Becoming a doctor’ is acquiring this ability to help a sick person get better. It is one of the most precious skills one can acquire in a lifetime.”

–Frank C. Spencer, MD, FACS, Cardiothoracic Surgeon

“Stepping into the operating room to perform heart surgery on a sick patient, being fully in control of the large team of people who are required to do the procedure, and feeling totally prepared to perform the task at hand is an unbelievable feeling that can barely be described.”

–Renee Hartrz, MD, FACS, Cardiothoracic Surgeon

“My life as a surgeon-scientist, combining humanity and science, has been fantastically rewarding. In our daily patients we witness nature in the raw–fear, despair, courage, hope, resignation, heroism. If alert, we can detect new paths to investigate.”

–Joseph E. Murray, MD, FACS, Plastic Surgeon

“There is a special joy that comes with the practice of surgery. Surgeons, indeed, are distinguished by the art and craft of their ability to perform surgical procedures or operations.”

–Thomas J. Krizek, MD, FACS, Plastic Surgeon

“Because I grew up with a strong family tradition of surgery, I also acquired a strong perception of the joys and demands of being a surgeon. Assisting people who are ill or injured has been and continues to be a rewarding dimension of the surgical profession for me. I would certainly pursue a career as a surgeon again without a second thought. And I would highly recommend the surgical profession to my children or any young person who is interested in a career that requires a lot of you and gives you even more in return.”

–George F. Sheldon, MD, FACS, General Surgeon

“The use of clinical knowledge and technical skills combined with the experience of dealing with a variety of people on a daily basis, make surgery a field that is not only challenging and satisfying, but fun.”

–George D. Wilbanks, MD, FACS, Obstetrician/Gynecologist

After medical school, how do you become a surgeon?

You must be registered with the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria. Please check here for the registration fees.

You must have completed a one-year internship program at a recognized hospital. Recently, MDCN introduced a centralized system for posting newly graduated doctors to internship positions in federal hospitals. For a list of hospitals currently in the program, please check here.

If you are a Nigerian, you must have completed the compulsory one-year National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) or obtain an exception.

You must pass the primary examination of either or both the two postgraduate medical colleges in Nigeria. The bodies are the West African College of Surgeons (WACS) and the Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria. The two examinations are equivalent. The examinations take the form of multiple-choice questions for both Colleges and they take place twice a year in Lagos, Abuja and Enugu. Please check the Colleges’ websites for further information regarding the exams.

You must obtain a training position with an accredited training hospital. Please check here for the list of hospitals accredited by the Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria and the West African College of Surgeons. You might have to do both a written and an oral interview to get this training job. Today, there is a lot of competition, so you need to be ready.

The Training

Junior Residency

This consists of 18 months of intensive clinical and academic training, with an emphasis on practical experience. You will be required to rotate among a number of subspecialties, including:

- General Surgery: 6 months

- Trauma Surgery

- Orthopedics

- Urology*

- Anaesthesia

- Paediatric Surgery*

- Cardiothoracic Surgery*

- Neurosurgery*

You will spend three months in each subspecialty except for General Surgery where you are expected to spend 6 months. The specializations marked with an asterisk (*) are optional, but you must complete at least two of them. In addition, you will be provided with a logbook in which you will record all the procedures you performed during your training.

The examination is conducted over a period of 2 to 7 days and follows the following format:

- MCQ and written examination on day 1

- Clinical examinations which is made up of a long case and short cases

- Viva voce

The methods are comparable to, but far more rigorous than, clinical examinations in the majority of medical schools. The Postgraduate college awards a prize to the top best candidate in any given exam for the year, allowing him or her to train overseas for six to twelve months.

Senior Residency

Passing the Part I examinations qualifies you as a senior registrar in your subspecialty. This may be the most significant time period for trainee surgeons, as this is when they learn the practical aspects of their specialization through apprenticeship. It has been said that surgery is both a science and an art; in this part of your training, you will learn the “art” of surgery. You should cultivate a close relationship with your consultants to facilitate this. This is also the moment when you begin making significant treatment decisions and gaining independence.

In contrast to many other specialties, the surgery senior registrar is typically the busiest member of the team, particularly during call periods. He reviews every patient who enters the unit during his call period, so he is quite busy.

Depending on the subspecialty, a senior registrar should be qualified to sit for the part two examinations between 18 and 48 months. Even though there may be some variations in the two Colleges as well as their subspecialties, the examination formats are similar for the two examination bodies, and they take the following format:

- Project Presentation and Defense: You will need to complete a project relevant to your field. The defense of this project is the first part of the examination.

- Oral Examination I

- Oral Examination II

For those specializing in orthopaedic and trauma surgery of the PMCN, a clinical examination comprising a long case, short cases and viva voce sessions are also held

Part II projects hints

- Begin to think about what your project is going to be as soon as you’ve passed the Part I exam. Choosing a topic is one of the more difficult hurdles to cross. Do a thorough literature search and read widely. PUBMED and GOOGLE are two good places to begin your searches. The local library in your hospital or university is another good place. the University College Hospital Ibadan has the best medical library in Nigeria, it is a good place to look for hard copies of journals; it also houses a separate section devoted to local and regional journals that you may need to add local flavor to your references.

- Also, the Post Graduate Medical College has a library which includes a section that contains all the previous projects. Going through these ones can offer valuable insights into the scope of what you can do and may help you to avoid duplicating previous work.

- Talk to your consultants, seek their advice

- If your topic is clinical, examine hospital records to determine its prevalence. For such a research, it would be bad to select a condition that is uncommon, as you may not have enough cases. I should know, as I faced a similar situation when preparing the proposal for my Part Two thesis. I abandoned my initial proposal since I did not get enough cases during the pilot phase.

- Ideally, within three months, you should have finished writing your proposal preparatory to submission.

- Choose a study with easily measured outcome parameters: comparative studies are among the best. Avoid such studies like “patterns of xxxx.” and “Epidemiolgy of yyyy” Most of the past studies were in these categories and examiners have grown weary of them.

- Know your statistics inside and out. Use the right analytical technique. You will undoubtedly benefit from reading my book “Getting to know SPSS” in this regard.

Please note that the two colleges hold their exams for each stage twice in a year: APRIL/MAY and OCTOBER/NOVEMBER.

And that’s all folks

Leave A Comment